Onchain CLOBs: The Endgame Exchange?

10 min read • June 26, 2025 Special thanks to Soumya Basu, Dominic Carbonaro, Jacob Everly, Chad Fowler, Benjamin Funk, Patrick O'Grady and Myles O'Neil for feedback and review.

The opinions expressed in this post are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the reviewers.

Introduction

Hyperliquid. The results speak for themselves:

- $248 billion perp volume in May (10% of Binance)

- $3.6B of USDC locked (tied with Base and only behind Ethereum and Solana)

- 11th most valuable cryptocurrency ($36.78B FDV vs Solana's $87.49B FDV)

- Airdropped $1.6B worth of tokens to its users

After the FTX implosion, conventional wisdom declared the exchange market saturated and the era of disruptors over. Hyperliquid's explosive growth shattered that consensus, proving one thing: the endgame exchange hadn't been built yet.

Hyperliquid is a custom L1 that supports its flagship product, the onchain Central Limit Order Book (CLOB). Some view its success as market-validation that onchain CLOBs are the endgame exchange, dubbing this next phase of onchain CLOB launches as the "CLOB wars."

On the surface, the proposition of an onchain CLOB is incredibly compelling. It blends the sophisticated trading capabilities of traditional finance with the self-custody and permissionless access of crypto. It also offers a potential path away from the impermanent loss and slippage issues that has plagued Automated Market Makers (AMMs) while simultaneously presenting an interface that institutional players are familiar with.

However, this narrative ignores the inconvenient reality that the onchain model is riddled with fundamental, perhaps fatal, flaws. Can an exchange that is significantly slower than Nasdaq truly be the endgame exchange? Is order flow transparency an advantage, or a bug that exposes traders to attack? Is the promise of "code is law" enough to compete with the insured, regulated titans of traditional finance?

This analysis argues that these are not minor hurdles, but structural disadvantages that create an opening for the true endgame exchange. We will deconstruct the onchain CLOB model to answer these questions and define the properties an endgame exchange must have.

Onchain Benefits

Self-Custody & Counterparty Risk Reduction

One of the most profound benefits of an onchain model is the radical reduction of counterparty risk. In the traditional model, traders must hand over their capital to the exchange, trusting that the institution will behave benevolently and competently. This creates a single point of failure where frauds, hacks, or simple mismanagement can lead to a total loss of funds. The industry-defining collapses of Mt. Gox and FTX highlight this inherent risk.

Onchain CLOBs fundamentally invert this relationship. By leveraging smart contracts, they enable users to grant limited, revocable permissions to the protocol to execute trades on their behalf. The logic is transparent and the rules are enforced by code. It replaces the opaque, trust-based system of a centralized entity with the verifiable, trust-minimized promise of "code is law."

Regulatory Arbitrage

It is well understood that going onchain is a way to operate outside of traditional regulatory perimeters. For exchanges, this benefit cannot be understated. In the highly regulated world of finance, launching an exchange is a herculean task. You need to pay a large upfront cost to acquire licenses, adhere to strict compliance regimes, and safeguard customer assets in flight.

By contrast, onchain CLOBs sidestep all of this by living in the global, permissionless onchain world. These platforms can, in theory, exist beyond the direct control of any single jurisdiction. They can:

- Cater to a wide user base with minimal barriers to entry (no KYC/AML policies)

- Expedite asset listing (no compliance requirement of a formal listing process)

This is known as regulatory arbitrage—onchain CLOBs can leverage the decentralized nature of onchain to do things that a regulated, centralized competitor simply cannot.

Onchain Drawbacks

A Millisecond is an Eternity

The gold standard for performance, Nasdaq's co-located matching engine, boasts round-trip latencies—the time from sending an order to receiving an acknowledgement—of sub-50μs. This near-instantaneous level of speed is gained by physically placing participants' servers next to the exchange's. To put that into perspective, light travels 15km or 9 miles in that same timeframe. It is physically impossible for any geographically distributed system—let alone blockchain—to compete with that speed.

The performance of even the fastest decentralized systems illustrates this gap. The dominant onchain CLOB today, Hyperliquid, boasts a median latency of 200ms, 4000x slower than Nasdaq. Solana's recently announced Alpenglow consensus protocol aims for 150ms, 3000x slower than Nasdaq. To escape this bottleneck, teams like Bullet have given up on geographical distribution in favor of a centralized sequencer L2 approach. They claim to achieve 2ms latency which, while impressive, is still 40x slower than Nasdaq.

For an endgame exchange, these speeds are simply not fast enough. The Investors Exchange (IEX) was famous for launching an exchange to mitigate the effects of high-frequency trading (HFT). The speed bump that they add to all orders is 350μs. If 350μs is a significant market-altering delay, then 2ms (2000μs) is a different league and 150-200ms (150,000-200,000μs+) is a different sport altogether.

Privacy Mirage

Every transaction onchain is recorded on a public ledger. While this transparency is crucial for verifiability, it also creates a glass house for traders—exposing every move they make. We saw this play out in dramatic fashion when trader James Wynn's $1.25 billion leveraged Bitcoin position on Hyperliquid dominated the news cycle. He alleged that the platform's public nature turned his trade into a target, enabling attackers to "hunt" his position and liquidate him.

Whether his claims are entirely accurate or not, the event highlights a deep-seated need for privacy. Centralized exchanges like Coinbase offer this implicitly: their internal operations are a black box, shielding participants from one another. Onchain, however, there are no shields.

In response, teams like Hibachi are turning to Zero-Knowledge (ZK) proofs to replicate the black box for traders. Yet, even these solutions have an Achilles' heel: the front door. The act of entering the black box is public. If the Ethereum Foundation deposits $50 million in ETH into a ZK trading venue, the world doesn't need to see their exact orders to guess what they're going to do.

The only way to avoid this information leakage would be to keep all assets within the ZK protocol permanently. The impracticality of this requirement leads us to the final drawback.

Unintentional Custodian

The "all or nothing" commitment demanded by a perfect privacy solution is a microcosm of a larger structural problem facing every onchain CLOB. The entire DeFi ecosystem is effectively a fragmented archipelago of blockchains, and each CLOB creates its own isolated, protocol-level silo within it. For a trader to participate, they must commit capital not just to a specific chain, but directly into that protocol's smart contracts. This introduces immense friction and risk, discouraging the free flow of capital that deep, efficient markets require.

This structure fundamentally changes the competitive landscape. An onchain CLOB is no longer just a technology provider; by requiring users to lock billions of dollars within its contracts, it becomes a custodian. Its value proposition shifts from trading features to trustworthiness, putting it in direct competition with institutions like Coinbase, BNY, Fidelity, etc. These institutions thrive in an open, interoperable ecosystem where capital held with one custodian can be deployed across numerous exchanges—a stark contrast to the closed, siloed model of onchain CLOBs.

In this arena, the onchain model is at a steep disadvantage. As of 2025, established exchanges compete on a foundation of regulatory compliance, robust crime insurance policies for digital assets, and FDIC pass-through insurance for USD balances. They offer a sense of security built on legal and financial precedent. An onchain CLOB offers the promise of "code is law," but it must convince a skeptical market that this new form of trust is superior to the established, insured, and legally accountable systems that dominate finance today.

Conclusion: The Race to the Endgame

While the fight for market share percentage can feel zero-sum, the exchange business itself is not—the pie is constantly growing. For context, the total monthly trading volume for crypto has surged from under $2 trillion in early 2023 to over $9 trillion in early 2025.

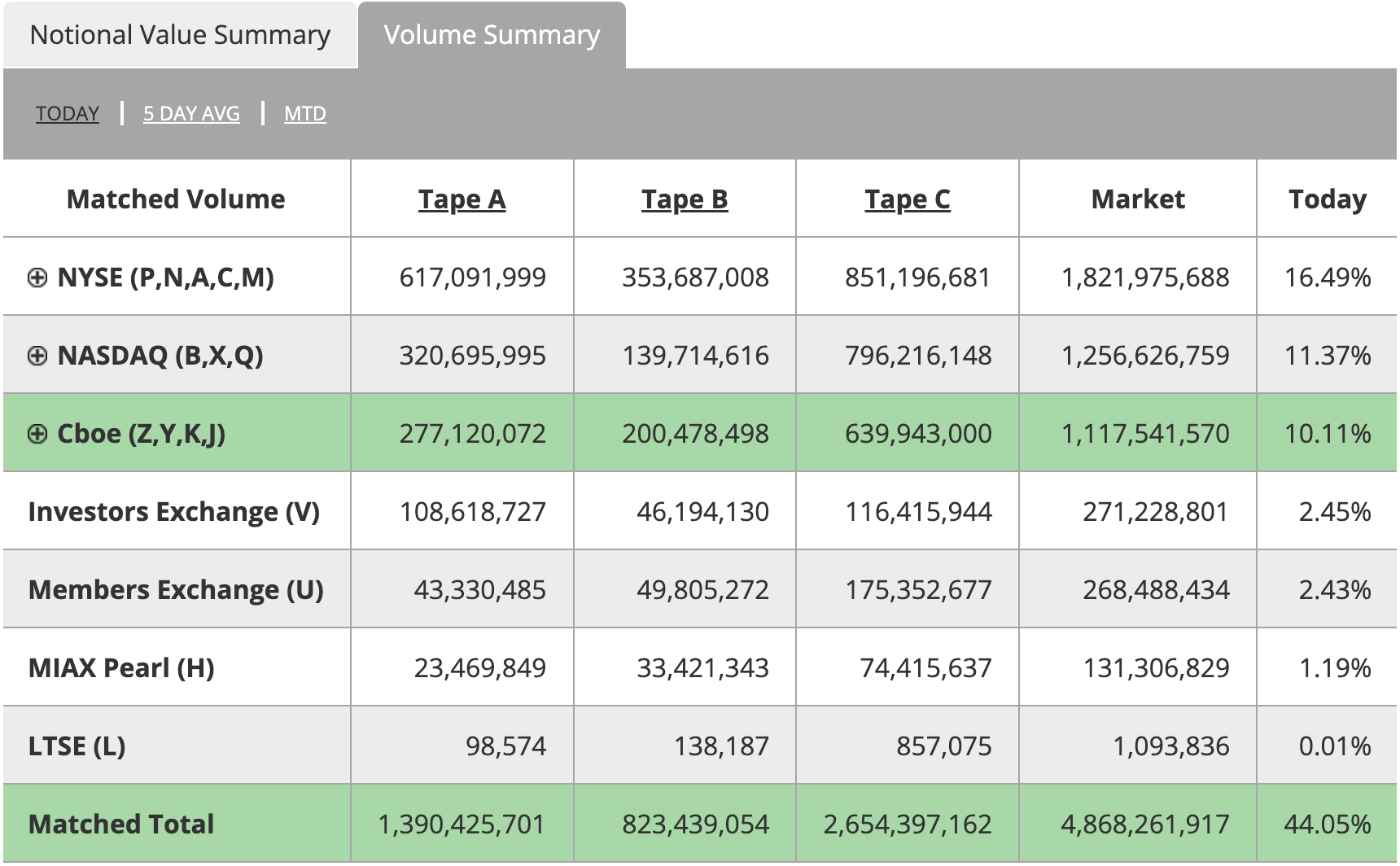

This growth creates room for multiple winners, a dynamic best illustrated by the world's most mature market, US Equities, which has no single dominant player:

The race, therefore, isn't to capture 100% of the market. It's to build the platform that flawlessly delivers the trifecta traders are starving for:

- Uncompromising performance. The raw speed, deep liquidity, and seamless user experience of a top-tier centralized exchange.

- Flexibility over custody. The freedom for users to choose their own asset security model: self-custody for sovereignty, or access to qualified, insured custodians for delegated peace of mind.

- Accountable and regulated execution. An absolute guarantee of fair trade processing, where market integrity is enforced by a legally accountable, regulated framework—a critical requirement for unlocking serious institutional capital.

The endgame exchange is likely one that nails this experience. The team that builds it will need to bridge two fundamentally different worlds by fusing the technological ethos of decentralization with the institutional bedrock of finance. Can a crypto-native team master the world of regulation, or can a TradFi titan genuinely embrace the principles of user-controlled assets?

The race is on to find out.